(first published July 6, 2012)

"We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies..."

(John Winthrop, governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony)

Some excerpts from a review by Dr. Pence of BONDS OF AFFECTION:

With most thinkers, Matthew Holland does not find eros in political life but neither does he build civic bonds on the philia of fraternal friendship. When he says 'civic charity' he means a civic life animated by agape -- that distinctive Christian love that "includes concern for another's standing before God even when others mean us harm." This of course has implications for how we treat our enemies and our fellow citizens...

Professor Holland finds agape informing the language and political goals of American leaders for two centuries by studying several key authors and texts: John Winthrop ("A Model of Christian Charity," 1630); Thomas Jefferson (rough draft of the "Declaration of Independence," 1776, and his "First Inaugural Address," 1801); and Abraham Lincoln ("Second Inaugural," 1865). Holland takes seriously Christian charity as a realistic way to deal with public life. He convincingly argues, that for both Lincoln and Jefferson, it was the realistic crucible of office which forged a deeper sensibility of the necessity of the bonds of charity in civic life. Holland's treatment of Jefferson is especially careful. Holland does not play the Christian alchemist turning Enlightenment rights into Christian love, but he reminds us that even the most rights-oriented of Jefferson's writings ends with a bond: "we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor." Holland reminds us this was no idle pledge. To secure that bond, one out of every hundred Americans lost their lives.

|

| Jefferson Memorial |

If Holland finds "bonds to the death" where others only found rights, he also finds analogical political forms in the New Testament where others tend to look for political narrative in the Old Testament alone. He quite rightly locates the sacrificial duties of soldiers in a pivotal moment in the Christian narrative -- Christ's Last Supper when he commands mimesis [imitation] and then sets out to lay down his life for his friends. Christian military men have always seen this obvious link -- political scientists almost never do. This is one of the great strengths of the book: Holland is both attentive to religious sensibilities and appreciative of military sacrifice. In fact, quite unlike the pagan warrior crowd, he shows that the patriotism of soldiers and the sacrificial love of agape are interlocking constituents of civic charity...

Here are four important ideas I learned... I may have heard variants on these ideas before, but Holland's charity theme clarifies and deepens the political union of men as fellow citizens:

1) All men possess rights but the point is to exercise them. This can only be done if we secure rights; and this is done by entering into a bond of agreement -- for this, we institute governments. No agreement, no rights. No civic love, no individual liberty. Possessing rights might be universal but exercising rights only occurs where rights have been secured by forming a real government in some time and place. Because of evil in the world this can only happen when men pledge their lives to protect these liberties. This is not a contract calculation by an individual, but an entry into a community of shared affections pledging personal honor and lives to each other and a new corporate entity.

2) Secular tyranny does not fear religion because it separates people but because it might unite us. Holland taught this by reminding us of Tocqueville's insight: "A despot will forgive his subjects that they do not love him as long as they do not love each other."

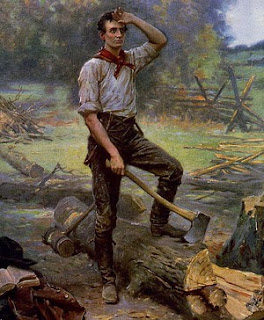

3) Lincoln's 1838 speech to the young men in the Springfield Lyceum was about giving up hatred and passions by living inside the law. Men must be united by civic affection to governance as well as each other. I was newly struck in that speech (having read it at least twice before) how much Lincoln felt he had to deal with men's hatred. Thus his language is built on authority and affection more than rights. At the Lyceum, Holland emphasizes that Lincoln does not soothe, but is demanding of the assembled young men. See the brave acts of the ancestors -- you benefit from this but as of yet you have done nothing to continue their work. (If only leaders, especially so-called conservatives, would so speak to young men at our elite universities and think-tanks with such demands.)

4) Here is Holland's eloquent description of political prudence in Lincoln: "To do this effectively meant for Lincoln assiduously gathering facts, contemplating history, anticipating implication, working out an argument against its best counterattack, and allowing time, circumstance, public promotion and private negotiation to settle things into a workable solution. His self-chosen metaphor was pilots on a western river who knew they wanted to get downstream but only steered from point to point as they could see, which was often not far."

[Professor Holland also provides] a powerful and sympathetic treatment of the much-neglected, but most important, novel in American history: Uncle Tom's Cabin.

|

| John Winthrop, who died in 1649, served as governor for twelve years |

No comments:

Post a Comment